That time I was turned back at the Ukrainian border

I learned, yesterday, that New Zealanders require a visa to enter Ukraine. I learned it from a heavily armed guard on the wrong side of the border. Since I didn’t have a visa, I was denied entry, and spent the next hour or so being gently but firmly ejected from Ukraine, and into the freezing wind.

Craig and I are fortunate travellers: most of the time, things go well. If they don’t, it’s often out of our control and we generally deal with the situation calmly, and just do what needs to be done to solve the problem. Sometimes, though, things go wrong and it’s our fault. Or, since I do most of the travel planning, it’s my fault — and I hate that. I don’t like being wrong and stuffing up travel plans hits all my buttons: I’m letting Craig down, I’m almost certainly wasting money, and I feel stupid.

So what happened?

Earlier this year, we decided to attend the Moldovan wine festival in October (regardless of visa hassle) and we were delighted to see that Moldova had changed their requirements and Kiwis could get in visa-free. And Ukraine was the same… or so I thought.

Arriving in Moldova was trouble-free, and we had a great couple of weeks tasting wine and exploring the country. When it was time to move on, we booked our first few nights’ accommodation in Odessa, and hopped on the early-morning train Ukraine-wards. Half an hour or so before we hit the border, I had the horrible thought that I hadn’t double-checked the visa situation. We’d bought a Moldovan SIM card a few days previously, so I could use my phone to look online, just as I had on the way to the airport to fly to Moldova. But this time, instead of a wave of relief, I felt a physical jolt in my stomach — New Zealanders DID need a visa, after all.

There was nothing we could do until we’d reached the border, or rather, the first stop after the border. Several armed guards boarded the train and one smiled at me as he sat down next to me on my wooden bench seat to enter my details in his hand-held device. “Nova Zelandiya,” he murmured, flicking through the pages of my passport and failing to find a visa. He made a couple of phone calls, called over another (sterner) guard, made another call, gave my passport to his colleague. A fellow passenger came over to translate for us. The second guard asked if I was a student; I said I had been studying in Spain. He took my student card and went away, and came back with bad news: I was denied entry.

We gathered our things and shivered on the platform, watched by a third, silent, guard, who held my passport in a gloved hand. When the train left 15 minutes later, my teeth were chattering, and I welcomed the return of the stern guard, who pointed at us and then at the silent guard, and declared: “Office. You go.” We went. The silent guard led us across the tracks to a car, and drove us several kilometres along potholed roads, back to the border. He led us down a dark corridor and ducked his head around a door to pass my passport on to the occupants of the room behind, before gesturing at a row of dilapidated chairs and indicating that we sit, and then left without another word.

Processing

It was cold in the corridor too. I pulled clothes out of my bag to layer over the ones I was already wearing and rubbed my hands together. The only light came from under a door at one end of the corridor, which occasionally opened to let a heavily armed guard pass by. The door we had entered by was thrown wide several times too, bringing light and a gust of freezing wind. People came out of the room where my passport was and walked away; we waited some more.

Finally we were invited into the tiny office, which spilled its warmth into the corridor as we entered. We sat on a wooden bench seat and defrosted while the female border guard whose office it must have been argued in Russian with another woman. The border guard scanned documents, entered details into her computer, printed things, folded paper, indicated that the argumentative woman could leave.

Then it was my turn. Another guard came in and they looked at my passport together; they asked me a question that I didn’t understand. The female guard started entering my details into the computer, muttering my name under her breath. I recognised the word for “surname.”

“Da,” I said. “Martin, familia.” That was probably right, because she repeated what I’d said with a questioning inflexion and nodded when I said “da.” (That’s “yes” around here.)

The second guard left the room and returned with a third person, whose name tag said Sergey. He said: “I’m going to translate for you, all right?”

All right? It was spectacular. Even though the final outcome was that I was “formally denied entry to Ukraine,” having someone there who could explain it to me in English made all the difference.

The border guard asked me to sign a document that basically said I’d been denied entry for not having a visa (Sergey translated), then printed me off a copy, gave me back my passport and smiled a goodbye. We thanked Sergey, then the other guard walked us to a passport control booth so Craig could get an exit stamp (HE was allowed into Ukraine, with his British passport; for some reason he decided to stay with me rather than going on), and we walked across a bridge to Transnistria.

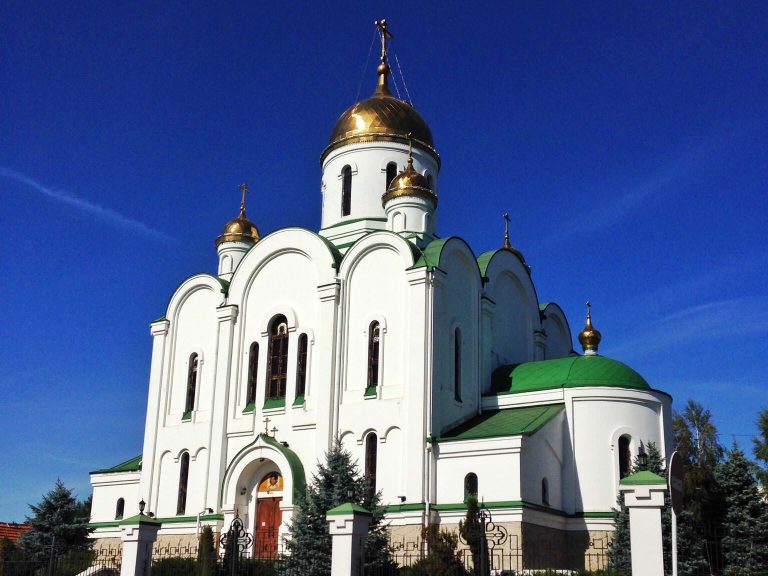

Transnistria

This breakaway republic is seen as part of Moldova by everyone except Transnistrians themselves, and they have quite strict border controls. We’d visited a week or so earlier, and hadn’t expected to be back, apart from crossing through on the train. The border guard directed us across a puddly carpark to another booth; the guard there looked at our passports and sent us back again. By this time the guard had changed and the new one let us through without demur. The vouchers she gave us indicated we had to leave Transnistria before 9.57pm that evening. Fine.

Not far from the border, we found an exchange office and changed $20 from our stash of emergency US currency into Transnistria roubles. At the ticket booth, we were told that there weren’t any direct buses back to Chișinău for a while, but we could buy tickets to Bender and return to Moldova from there. At Bender, we had enough time to buy tickets, get a coffee, and spend our remaining roubles on a bottle of Kvint cognac at the bus station store before the minibus jerked its way out of the station. The border with Moldova wasn’t far away and posed no problems: a guard boarded the bus, took our vouchers, and got back off again.

Back in Moldova

I used my phone to start looking for accommodation in Chișinău, and sent messages to our AirBnB host in Odessa and our Ukrainian friend Yuriy, asking if he could find out if I needed a letter of invitation to get my visa. He promptly set off on a mission across his city to write the letter himself, but was foiled by bureaucracy. “We don’t have any invitation blanks,” he was told. “We might get some after the elections.” The elections are in two weeks: not so helpful.

By the time we’d checked into our new apartment in Chișinău, it was too late to go to the Ukrainian embassy to start the visa application process. More online research suggested that New Zealand citizens didn’t need an invitation letter after all; perhaps I’d read that all those months ago and misremembered “no invitation required” as “no visa required”. I still felt wretched.

To the Ukrainian embassy!

This morning, I saved all relevant documents onto a pen drive and set off across town to Get My Visa. I printed off my insurance, flight and accommodation documents in a hotel, and arrived at the embassy to find a locked gate. The security guard indicated an intercom and I embarked on a friendly conversation with a disembodied voice. The voice informed me that the embassy was closed, today and tomorrow, as it was a Moldovan holiday. However, if I came back on Thursday at 9am, I’d probably have my visa on Friday morning.

“How much will it cost?” I asked.

“Umm, eighty… no, I don’t know. Come back on Thursday.”

“Yes, but, how much money should I bring? Will a hundred dollars be enough?”

“Yes, eighty, a hundred, one twenty. Like that.”

“And do I need to bring anything?”

“No, just you.”

“Me, my passport, and money, right?”

“Yes. See you Thursday.”

I felt inexplicably cheerful as I strode away towards the bus stop for a ride back to the centre of Chisinau. I might not have gotten my visa, but at least I knew where I stood: I was embarking on another Adventure in Bureaucracy.

I’ll let you know how it goes.

I’m glad I read this. I could have easily done the same thing. I never would have guessed we required a passport to go to Ukraine.

Yep, passports are pretty important. Visas, too!

Indeed, Ukraine is one of three European countries (the others being Russia and Belarus) which do not accept ID Cards from EU countries, but strictly require passports.

I have a ‘denial’ stamp on my passport from Ukraine as having a Turkish passport, they turned me back because I didn’t have a return ticket. This is so dumb if I want to do something or planning to stay there illegally showing a 20€ ticket is not a big deal. Bureaucracy sometimes killing me.

we don’t need visa from Ukraine btw.

Yeah, we’ve come across that rule in other places too. I think it made sense in the past, but doesn’t any more — it’s so easy to get a ticket to leave these days.