How to make sherry

Although it’s unfair to judge something before you try it, sherry’s reputation as a drink for old ladies meant that it has never been my first choice for a tipple. However, it turns out that sherry is fascinating — the process of making sherry is unlike any other wine-making system I’ve ever encountered. Variations on how to make sherry produces wines for every palate.

Sherry is a denomination of origin product

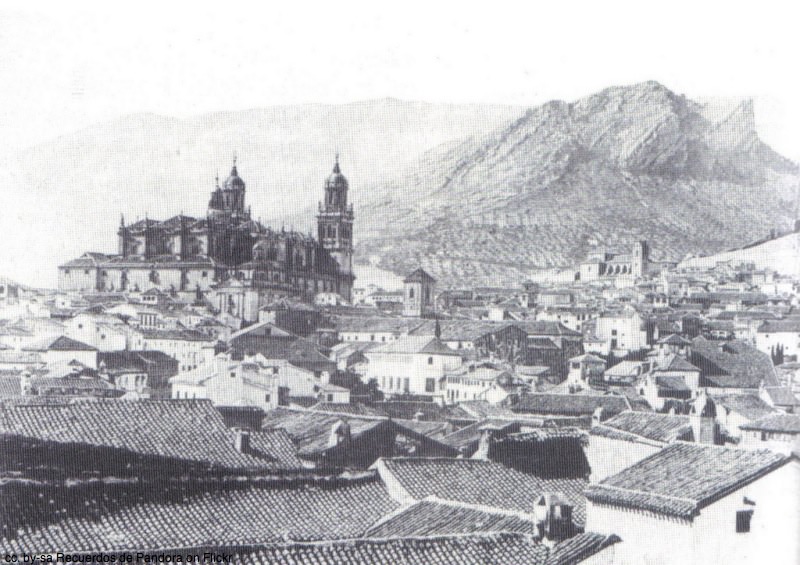

Like Champagne, a product can only be labelled as sherry if it has been produced in a strictly defined area. In this case, it’s a section of Andalusia known as the Sherry Triangle, which is bordered by the towns of Jerez de la Frontera, Sanlúcar de Barrameda, and El Puerto de Santa María.

You can try making a sherry at home, but it will obviously be a sherry-style wine instead of a true ‘Jerez’ sherry.

What grapes are used in Sherry?

Just three types of grape are used to make sherry — Palomino, Pedro Ximenez and Moscatel. By far the most common is Palomino, which is used for dry sherries, while Pedro Ximenez and Moscatel are grown to produce sweet sherries with the same names, and blends like Bristol Cream.

Grape Picking and Making Mosto

The grapes are picked in September and are pressed to extract the juice. However, the skins and stalks are all left in the mix, which is called must (or mosto in Spanish).

The must is put in stainless steel vats and left to ferment until the end of November. The result is a dry white wine (also called “mosto”) with an alcohol content of about 11-12%.

Can you drink sherry Mosto?

Visit Jerez in November and December, and you’ll see signs in restaurants advertising mosto — it’s a seasonal specialty. You can also visit seasonal restaurants called mostos for simple, tasty meals and a drink or several of (you guessed it) mosto.

Using Soleras and Criaderas when you Make Sherry

The mosto wine isn’t just thrown into a barrel and left to age. In the wine cellar, barrels are stored on their side, in pyramids of three or more.

The lowest level of barrels is called the solera (from the Spanish word for “floor”, suelo), while the other levels are known as criaderas (“nurseries”).

Wine in the solera level is ready to drink, but winemakers remove just one-third of the sherry from the barrels to be bottled. The rest remains behind, and the space left in the barrel is filled with sherry from the first criadera.

The empty space in the lowest barrels is filled with wine from the second criadera, and so on. The new wine is added to the highest barrel of the stack.

The barrels aren’t filled to the top, though, about one-sixth of the barrel is left empty to allow the wine to have contact with the air.

This system helps to control the standard of sherry that’s produced, as the resulting wine is a mix of harvests. This also means that most sherries aren’t labelled with a year of production. With ancient soleras, you might have traces of wine that are dozens of years old.

Flor or no flor?

Sherry is a fortified wine, which means that extra alcohol is added at some point in the winemaking process. Depending on how much is added, and when, you get very different types of sherry.

Fino Sherry

In the case of Fino, the spirit is added at the beginning of the process, but only enough to bring the alcohol percentage up to about 15%.

Because the alcohol level of the wine in the barrels is so low, a layer of yeast called “flor” grows on top of the liquid, preventing the air from having contact with the wine. The yeast feeds off the sugar in the wine, and the result is a very dry sherry.

Amontillado Sherry

Amontillados start life like Finos, with a layer of flor. But after two or three years, more alcohol is added, which kills off the yeast and leaves the wine in contact with the air. This allows the wine to start to oxidate, which means that it becomes darker in colour.

Oloroso Sherry

Olorosos have more spirit added at the beginning of the process, taking the alcohol level to about 17% — which means that flor never grows and the wine has contact with the air right from the beginning. Olorosos are a lot darker than Finos and Amontillados because they’ve had more time to oxidate.

Sweet sherry wines: Pedro Ximenez, Moscatel, Cream and Medium

To make sweet sherry wines, Pedro Ximenez and Moscatel grapes are used.

The grapes are left in the sun to dry for a day before being pressed, and the grape spirit is added to a higher percentage at the beginning of the solera process, which means that no flor grows in the barrel.

In addition to being sold as a stand-alone wine, Pedro Ximenez is added to Fino, Amontillado and Oloroso wines to produce cream and medium sherries. For example, Harvey’s Bristol Cream is a mix of Pedro Ximenez and Oloroso wines.

Visit Jerez to Taste Sherry in Spain

A great way to get your head around the different types of sherries is to taste them — and this is best done in the sherry wineries of Jerez itself. There are dozens of bodegas (wineries) in and around the city, and many of them offer tours in English — which end with a tasting. Yum.

Read more about Jerez, Spain:

- Sherry Tours – The Best Wineries of Jerez (Visited and Reviewed)

- Christmas in Jerez, Spain

- How to make sherry

- Spain travel

Tours of Jerez de la Frontera

Do you like sherry? Are there good places to taste wine near you? What’s your favourite thing to drink when you travel? Leave a comment below.

Great article – thanks! My wife and I are from Northern California, and were only recently introduced to the Joys of Cream Sherry while staying at a lovely B&B in Carmel, CA – they served Cream Sherry as the 5:00pm aperitif in our rooms before dinner – yum! Since then I have spent some time researching sherry, and am both amazed and delighted at the unique creation process, really like nothing else. My family lineage also happens to be from Spain, which makes the history of Sherry even more interesting, and we are making plans to visit Andalusia (along with the rest of Spain) in the near future. Keep writing these interesting articles!